The Terroir of Everything (Scraps 05)

An exploration of the taste of place (via the medium of audio)

This is Scraps, a monthly (ish) subscriber essay series. This one is available to everyone to read. If you like it, I’d hugely appreciate upgrading your subscription if you’re able to as it makes it possible for me to create more audio and written work for Lecker. Thank you!

Remember you can listen to all Lecker main feed episodes for free on all good podcast apps.

What does the word terroir mean to you?

It isn’t as old as I thought it was. While the usage of the word can be traced back centuries, it has historically been in the explanation of agricultural activities. Makes sense, given that it can be translated roughly from French as ‘soil’, or, slightly more ambiguously, as ‘region’. The understanding of the word to define how place, taste and quality are interconnected in particular crops, or foods, however, doesn’t even date back two centuries. The 1855 Bordeaux wine classifications are one of the first recorded attempts to connect the quality of a product to its place of origin.

Since its origin of use, it has been one of humankind’s most successful and effective marketing tools; imbuing foods with their own terroir of story as well as that of the land. This story is easier for me to recognise and then articulate than the flavours of particular varieties of grapes, or the tasting notes of the roasted beans, or how the condensation dripping from the walls of the cave washes the rind, or something. Knowing the story of something has an impact on our experience of eating or drinking it, undoubtedly, which is why packaging is such a lucrative industry.

Terroir isn’t something I’ve talked about much, not sincerely anyway. I’ve only ever pronounced the word with a slight shrug and a self-conscious eye-roll. Like talking about wine generally, I don’t feel qualified. How could my uncertified tastebuds ever discern anything meaningful? When I made the series Good Bread in collaboration with Farmerama, I loved recording Ruth Levene and Kimberley Bell read out descriptors they had collected during sessions with hospitality workers in which they were encouraged to taste different wheats in the form of cold, unsalted pasta, an endless list of beautiful seemingly unconnected words and phrases. Honey, buttery, oily, courgette, pumpkin seed, chestnut, meaty, lactic, brown butter, lard. It reminded me that we can access this ability to taste at any point, but we need to use it or lose it. “What else have we dumbed down and what are we missing in terms of our own ability to make these observations and judgments that might actually be quite helpful?” reflected Kim.

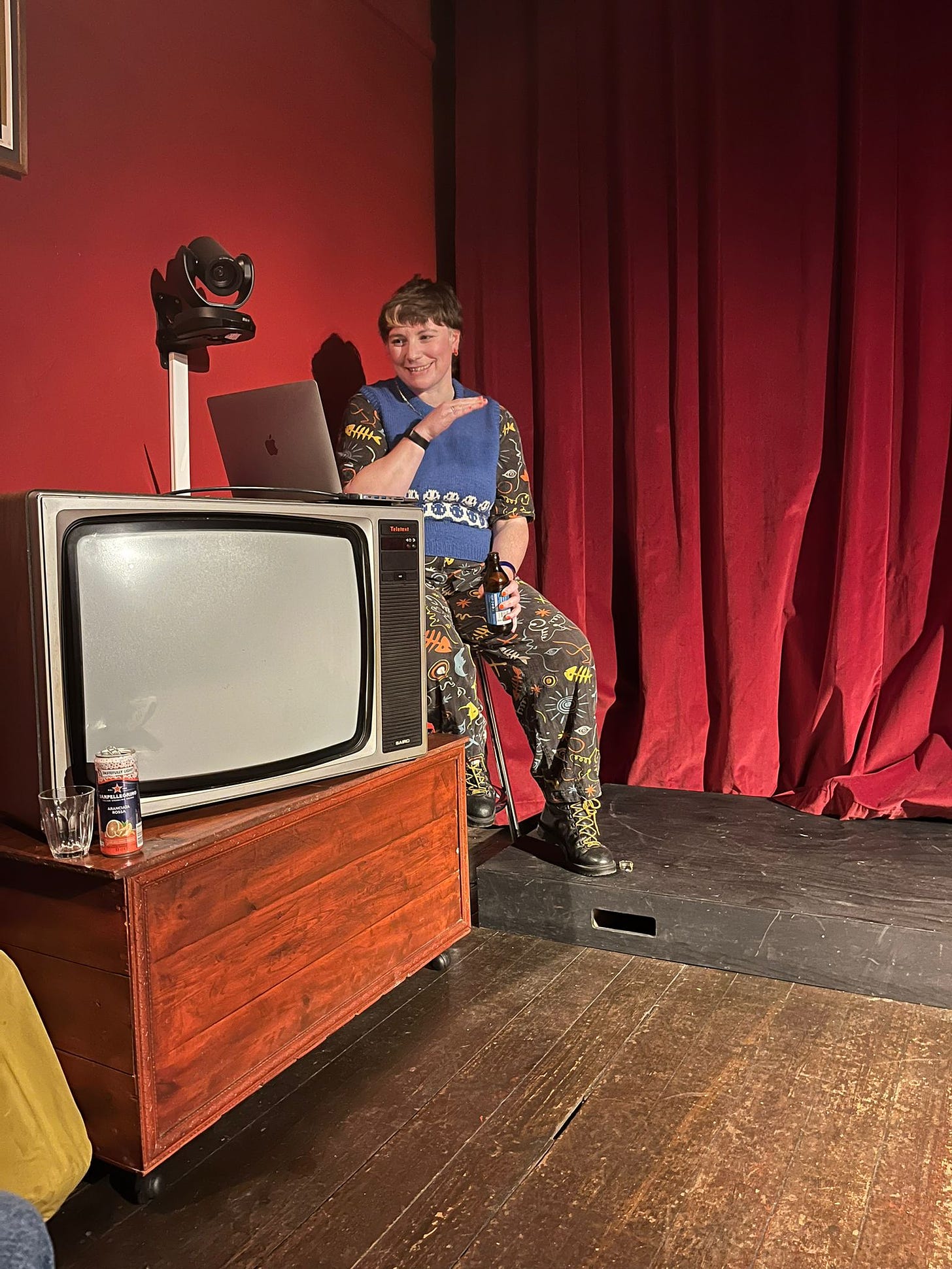

I recently curated and hosted an In The Dark event at XMTR Audio Arts Festival in my home of St. Leonards-on-Sea. In The Dark is a long-running series of sound events originally founded by Nina Garthwaite and loosely connected to the idea of ‘cinema for the ears’. Events generally involve audio playouts or performance that lean on creative or artistic audio making rather than any visual element. It has been a big part of my inspiration and desire to produce creative audio over the past decade and it was a real honour to be asked to be asked to do it, especially as the venue was the beautiful velvet seated and curtained Electric Palace in Hastings Old Town: putting cinema in cinema for the ears. I decided that for the event I would curate pieces around the theme of terroir.

“I had to look it up!” a radio producer friend of mine told me after I mentioned to her what the theme of this event was. The funny thing is: so did I. And even after I did…I still can’t really explain it. Something about how the composition or characteristics of the soil or other elements of the landscape make their way into certain types of food, either through the roots of plants or through the mouths of the animals who eat them? The idea seems slippery but the word sticks in the throat. Native English speakers struggle to spit it out. It’s not translatable, we’re told, so the implicit understanding is that you must choke and gargle your way through the double R in order to earn the right to use it sincerely. The foods with which it is commonly associated: first wine, and now also cheese, coffee, beer, are intimidating to talk about without qualification or experience. But these foods are not grown or produced in a vacuum. Like everything we eat, they are processed at the hand of humans and/or machines. If they have terroir, then doesn’t everything?

You can access the full playlist of works I played at the event here:

Beginning at the beginning, I thought that, before I blasted the idea out of the water in public, I should probably at least attempt to understand the scientific or geological argument for terroir’s existence.

“The first thing I would ask you is, what is soil?

Soil is the unconsolidated cover of the earth. Soil has a mineral component and an organic component. The definition of soil also includes water and air. An average soil has about…maybe 45% of it is a mineral component, 5% is organic, and then that other 50% is water and air that are kind of transient within the soil.

That mineral component is completely derived from rocks. It can be derived from rocks that are right there, what we would call residual parent material. So the bedrock itself is actually forming the soil.

Is soil decomposed rock, or?

Yeah, absolutely. It's decomposed, broken down pieces of rocks.”

The geologist Brenna Quigley, a specialist in hard rocks, gave a detailed interview to the podcast I’ll Drink To That about the connection between rocks and soil. In it, she explains that her geological interest in terroir in the wine industry came about because she sees the plant at the heart of its production – the grapevine – as a unique one thriving on residual soils (ie, a soil formed from broken down bedrock). “The vines actually don't want all of the nutrients that other crops do in order to do well, and especially in order to make quality interesting wine, they want some sort of a balance between struggle and thriving,” she said.

If you’re at all interested in the geology of terroir, even as someone who (like me!) knows next to nothing about it, I really recommend listening to the whole episode because it really is packed full of fascinating details that I can’t do justice to in a short summary. But just to finish, towards the end of the episode Quigley talks about how different terroirs all have what she calls a “different limiting factor” that changes what the most idea terroir of that region is. It could be water, or disease pressure, or temperature.

“It's actually a little bit contradictory when you're thinking about things like, oh, well, okay, so what's the best terroir? The difference is what's most important is going to be different depending on all of the factors that are going into play in that one location.

That's one of the reasons why you can't go to France and then come back to California and say like, I got it figured out. This is what we need to be looking for. It's part of a context.”

And this context that she talks about is arguably more than just geographical and geological conditions. In another great podcast episode on terroir, Vermont and the Taste of Place from Eat This, host Jeremy Cherfas interviews chef and cultural anthropologist Amy Trubek about her work on terroir, which focuses on maple syrup and dairy. Cherfas asks Trubek: “What is it about the Vermont terroir that makes Vermont cheeses sought after and highly regarded? How do they differ in that respect from, say, French Comté?” Her response is that….they’re both “excellent.” And that “from a purely sensory point of view, I don't know if I would say that you're gonna say that one is better or worse.” But, she continues, the terroir of Vermont specifically needs to be seen within the context of cheese production within the United States as a whole, which is almost exclusively industrialised.

“So the number one cheese produced in the United States is mozzarella cheese for pizza. And the majority of cheese consumed in the United States is consumed melted, either in forms of pizza or nachos. So the fact is, it's the fact that that these people are making a small farmstead, what you would call kind of sensory quality based cheese, is what makes it different in the United States.”

Cherfas presses further: “Is there any way in which knowing the story of the cheese or the cheesemaker, that this cheese was made by a ‘litigator who wanted to go back to the land’? Is there any way that that affects, I don't know how you, how you taste the cheese?”

I found Trubek’s response so striking.

“Tasting a cheese is what we call an experience of intersubjectivity. You both have an experience that's a sensory experience, that you could evaluate sort of separate from the story. But the story is the way in which, in a sense, you experience the meaning of the sensory experience. And I would say that it's the combination of the two that is making Artisan Cheese particularly compelling.”

At some point during the research for the Terroir event I found myself watching cultural historian Andrew Hussey eat a plate of lobscouse at Maggie May’s in Liverpool. The pale brown stew is “firm enough for a mouse to trot over” and the shocking fuchsia of the accompanying red cabbage, on the side in a little bowl, brings vivid life to the plate. He makes the case for the terroir of Liverpool being that of its sea and port; of the Scandinavian and Germanic influences that arrived this way on its history and culture. On screen, jaunty illustrations of different countries’ own versions of lobscouse appear to demonstrate the movement of culinary practices but also the distinctiveness of how these are adopted in each place. “Liverpool is famous for lots of things and rightly so,” intones Hussey. “Music, football, humour, politics. All of this is part of the terroir here.” At no point in conversation about the scouse with the chef do they really get into provenance of the ingredients he uses, and whether locally grown vegetables or locally reared meat gives the dish a unique taste of place. It is implicitly understood that the scouse is inherently Liverpudlian, and that is what gives it its terroir.

Hussey’s programme The North on a Plate appeared several pages deep into one of my numerous google searches. I was extremely excited to find it and immediately emailed a begging request to a friend (who shall remain anonymous for legal and professional reasons) with access to the BBC archive. It was only once they’d found it and generously WeTransferred it back to me that I realised I’d misread BBC Four as Radio 4 and the programme was actually for television not radio. I couldn’t in good conscience pretend television was radio to a cinema room full of listeners (and most likely 90% radio producers) so I reluctantly left it out of the event playlist.

I was particularly sad to have to do this because the programme tapped into my slightly complicated and entirely un-footnoted feelings about the idea of terroir. In it, Hussey casually chucks a grenade into the traditional notion of terroir as it’s generally understood in gastronomy and introduces his own theory of terroir: that of culture and of story.

In one segment, Hussey subverts a Wigan pie-eating tradition. He invites a group of local bikers, including the reigning pie-eating champion, to a pie stall at a local covered market, under the premise of a mini pie challenge for the cameras. Once they’re all assembled, however, he reveals that the actual main competition is to give him their best memory of Wigan pies. “The real winner of this competition is going to be the person who comes up with the best story of what pies mean to them. It's the big, existential pie eating champion we're looking for.”

The stories spill out: Everton Football Club. School Dinners. Eating homemade pies at Grandmas and getting it all over the table. Motorbike rallies. Next to a cold pint of Tetley’s Bitter.

“I'm pleased to say that what we've found out is that pie eating in Wigan is not just a tradition, it's also a palimpsest. which means the past and the present and the future,” announces Hussey. “Do Wigan pies have terroir? I think they must have.”

It was the kid who ate pies at his grandma’s who was crowned existential pie eating champion, by the way. A generational wealth of food stories is always powerful currency.

I noticed that even in trying to expand the understanding of terroir, in breaking down the vineyard fences, I was clinging on to a kind of romance. Holding on to an appealing notion about deeper meaning beyond the immediate present moment experience of what we eat and drink. But really, pushing the boundaries on the definition of the word and the idea should encompass the opposite of romanticising produce. It should be able to swell to contain all of the conditions of global food production, appealing and comfortable or otherwise.

I was amused to read about ‘merroir’: the terroir of the sea, often used in connection with oysters, and also ‘aeroir.’ Through the latter, I found a short feature about an immersive art project by Zack Denfeld and Cat Kramer. In the Smog Tasting Project, the artists harvested air pollution in cities around the world by whipping up egg whites into meringues on street corners. Denfeld comments:

“When we think of huge forest fires or air quality that's gotten worse over many, many decades, it's something we can barely touch with our minds. And so I think using flavour and taste and making it particular in that way, it's a way of actually using language or metaphors or experiences that are understandable at the scale of our bodies to then say, Oh, well, you know, Beijing tastes really burning in my throat, but Mexico City tastes really sulphuric. Why do those taste different? What are the things that are contributing to them?”

And in a vivid essay for Emergence Magazine, Lily Kelting explores related ideas through the terroir of milk in her home of Pune, India.

“While terroir, the original French concept, is perhaps outré, its literal meaning, taste of place, is a useful and generative idea. Use of the term is booming, alongside more explicit concerns with local eating and farm to fork dining.

But I'm compelled to wonder, because I am, by both scholarly training and disposition critical, because I live next to an open sewer, what places does the concept of taste of place exclude? Is there room enough here for the milk I boil for my sons each morning? Can we talk about the taste of place when that place is an edge-place, a developing place, an ugly place, a no place?

Is there room within the concept of terroir, I guess I'm asking, for me?”

I was so grateful to find this essay as I had been thinking a lot about the places we generally refer to when we talk about terroir: regions of relatively wealthy, Global North countries with certain types of landscape. Kelting’s descriptions of the cattle of Pune and how they are fed within this urbanised, polluted city seem to embody the idea of terroir like nothing else I’ve encountered.

“Cows are routinely fed the stalks of sorghum and millet, agricultural byproducts left behind after producing the millet flowers that are the staple grains in Maharashtra. Feeding the otherwise inedible stalks to cows reduces waste, essential when the profit margins for agricultural workers are already so tight. The economy of the urban dairy has no choice but to be circular.

Sugarcane is the real cash crop of this region. Juiced sugarcane stalks seem to be nothing but tuft fibres, but they're still chipped into small pieces and fed to cows.

Of course the milk tastes sweet.”

I also wanted to think about and reflect on the importance of connection to land, and what happens when people are displaced – often violently – from their home. How can we think about terroir without considering this? In a beautiful documentary for Outside/In called The Acorn, an Ohlone man named Louis Trevino and his Ohlone partner, Vincent Medina, are on a journey to bring acorn bread, and the language and traditions connected to it, back to the Ohlone people. Trevino and Medina talk about the painful reality of the severing they have experienced from their indigenous culture as a result of Spanish colonisation in what is now known as California.

“I mean, we just have to look to the name of the city, Oakland, to, you know, to see that it's […] because of all of the oak groves that have been, and those have been nurtured by our people for generations. We taste acorns from those same trees that we know our ancestors did. The truth is, though, that with the city around us today, those oak groves are becoming increasingly threatened. We can go up into the hills and gather some acorn, but it's harder and harder for us.”

When I interviewed N.S. Nuseibeh about her book Namesake, a jolting memoir about Palestinian identity through the lens of her 7th century warrior woman ancestor, she talked about the special character and taste of the aubergines from the West Bank village of Battir. They make one of her favourite dishes, Bitinjan Battiri, almost impossible to recreate outside of Palestine. And it was during this conversation that I really started to think about the terroir of all things thanks to Nuseibeh’s thoughts.

“People who are wealthy – not me! – will pay a premium for like wine that comes from particular grapes in particular areas because they can taste the earth through the wine or whatever, that's what they say. And it's absolutely the same thing when it comes to you know, things like aubergines will also have the terroir in their essence and, and the way they're grown and the organisms that they are.

It's so strange that we don't think about the connection between food and place or produce and soil in that way when it comes to more general foods. I guess we've just gotten so used to things being globalised and everything being like available in plastic wrapped packets and Sainsbury's from all over the world.”

And what happens to a taste of place when that place is violently contested, its crops destroyed? Nuseibeh also talked about Vivien Sansour and the Palestine Heirloom Seed Library she founded, preserving culturally and locally significant crop varieties. Interviewed on the podcast Stories From Palestine in 2020, Sansour talked about the symbiotic relationship between seeds and soil.

“The farmers say: this seed knows the soil. This seed has over the years co-evolved with this soil. And so that's really important to understand. We should take care of our soil the way we take care of our seed because the seed doesn't exist on its own by itself.”

In the episode, Sansour talked about a particular variety of heirloom wheat, Abu Samra, which local musician Zaid Hilal (also part of the episode) wrote a song about. <iframe width="560" height="315" src="

title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share" referrerpolicy="strict-origin-when-cross-origin" allowfullscreen></iframe>

When I started writing up my scattered and disparate notes for this piece, I realised that – coincidentally – the Food Chain had published the episode Can you taste a place? the week after I did the event. In it, they looked at the terroir of honey, a geneticist working on barley for whisky production, and at a vertical farm growing lettuce in Liverpool. The thing that really struck me about the latter was that, when asked about whether lettuce grown in this strange, artifically lit, soil-less environment could have terroir, Peter, the operations manager, interpreted the question in a way I never would have predicted. “We could grow a lettuce in here to basically, conditions that are replicated from, say, Genoa or Sicily, so we could have the same temperature, same lighting, same nutrients.” How interesting, that he immediately started talking about essentially recreating terroir! Not whether the soil-less vertical growing system could have its own taste of place.

“Is it as simple as saying heat plus light plus humidity plus nutrients equals terroir, a sense of place and taste?

To a degree, yes. There's other things in there that, obviously, in a normal vertical farm system, you wouldn't have. And that's the microbes you have in the soil, which will affect nutrient uptake and plant resistance and plant health. There's no reason why you couldn't put that into a vertical farm as well. So there are people looking into those particular types of things, looking at microbe interactions with the plants, and what would be beneficial for the plant itself. But apart from that, then, yes, I mean, terroir is probably as simple as saying that the particular conditions that you have at that particular place, that you'll grow in your plant.

What about the romance? What about the culture, the people, the hands that have worked the soil?

Yeah, I mean, you lose that in a degree.

And will that affect the taste?

I don't think it would, no. But it does kind of affect the romance a little bit.”

I encountered so many interesting pieces for this event and just couldn’t include all of them. Here’s a few that I didn’t have room for but are fascinating and relevant nonethless:

Taste of Place: Dr Anna Sulan Masing’s deeply personal Whetstone series about pepper, Sarawak and memory.

Smoky Wines: forest fires have had a huge impact on Australia’s wine industry and I admired the resilience and innovation of this producer. Also Wine in a changing climate.

On merroir: Oyster fishing threatened by E-coli in the water.

And notable mention to two very early BBC radio documentaries, one of which was, I believe the first broadcast to ever use recorded ‘actuality sound’ captured on location rather than just reporting. They may or may not be relevant to this topic as despite my best efforts I couldn’t access the full versions to listen! If you have any leads as to where I might be able to, let me know…

‘Opping ‘Oliday: Laurence Gilliam’s 1934 documentary about East Enders travelling to the hop gardens of Kent to help out with the harvest.

The Classic Soil: Olive Shapley’s 1939 documentary offering what the Radio Times called "a microphone impression" of Manchester "today and a hundred years ago", drawing inspiration from Friedrich Engels’ Victorian survey, The Condition of the Working Class in England.